Venous thromboembolic disease encompasses both venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Pulmonary embolism occurs when a thrombus, usually clotted blood and less commonly tumor, migrates breaks off from the location where it formed, and migrates into the pulmonary circulation. Risk factors for thrombosis include primary hypercoagulable syndrome, recent surgery, pregnancy, prolonged immobility, malignancy, and oral contraceptive use. Patients variably present with acute dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, tachypnea, tachycardia, and hypoxemia.

Segmental embolus. Lateral basal segment right lower lobe embolus with associated wedge-shaped peripheral opacity corresponding to a small pulmonary infarct.

Occasionally large emboli can obstruct the central pulmonary arteries (saddle embolus) and severely compromise air exchange and circulatory function, in which case, the clinical presentation may include circulatory collapse.

Central “saddle” embolus. Large clot within the right and left main pulmonary arteries.

A negative serum D-dimer effectively excludes pulmonary embolism in patients with low to moderate pretest probability, based on a collection of clinical findings known as the Wells criteria:

Wells Criteria for Prediction of Pulmonary Embolism

Clinical signs and symptoms of DVT + 3

PE is #1 diagnosis OR equally likely + 3

Heart rate > 100 + 1.5

Immobilization at least 3 days OR

surgery in the previous 4 weeks + 1.5

Previous, objectively diagnosed PE or DVT + 1.5

Hemoptysis +1

Malignancy w/ treatment within 6 months or palliative +1

Risk

< 2 low risk (1.3% incidence)

2-6 Intermediate risk (16.2% incidence)

>6 high risk (37.5% incidence)

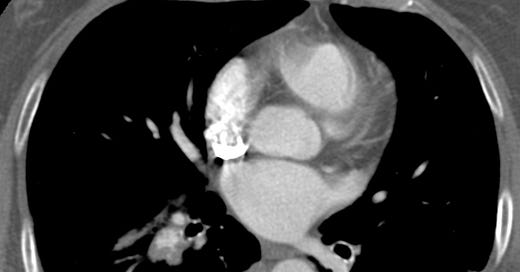

Patients who are considered to be at high clinical risk, and those low to moderate risk who have an elevated D-dimer, should undergo CT angiography optimized for pulmonary arterial opacification. When positive, CT demonstrates central nonenhancing thrombus surrounded by contrast material. If right heart pressure is increased, the ventricular septum may appear straightened or bowed toward the left ventricle and contrast may reflux into the hepatic veins.

Increased right heart pressures due to large pulmonary embolus. The right ventricle is enlarged with straightening of the intraventricular septum.

Chest radiographs in patients with pulmonary emboli are typically normal or nonspecifically abnormal. Atelectasis, pleural effusions, or small peripheral opacities are sometimes encountered, but they can be seen in many other conditions.

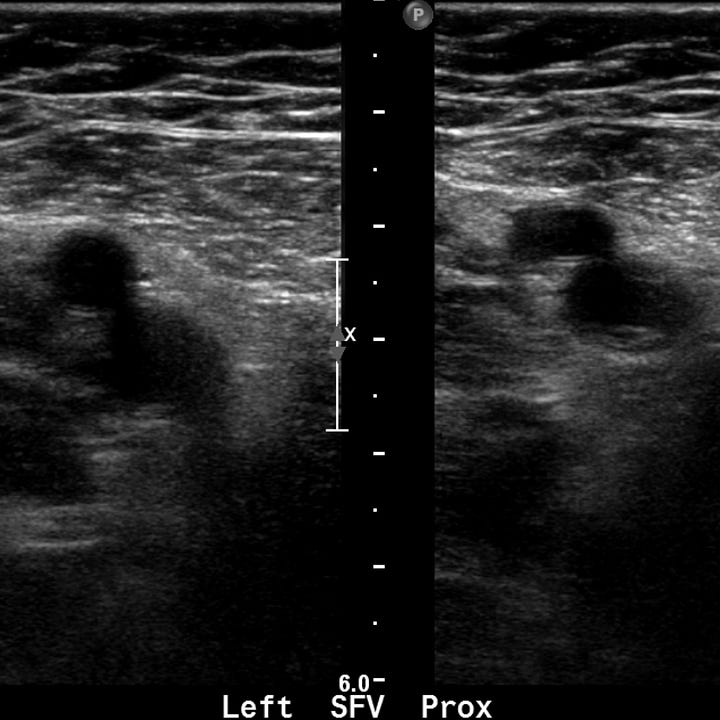

Lower-extremity deep venous thrombosis (DVT) is a common disorder with predisposing factors that include immobilization, prior DVT, recent surgery, hypercoagulable syndromes, indwelling central venous catheter, increased estrogen state, and malignancy. Clinical findings include pain in the calf or thigh, unilateral leg edema, and warmth or tenderness. Ultrasound is most frequently used to differentiate DVT from other clinically similar entities such as cellulitis, ruptured Baker cyst, superficial thrombophlebitis, chronic thrombosis, and venous insufficiency, all of which can cause lower-extremity edema.

The single most reliable diagnostic finding is a non-compressible deep lower extremity vein. Other ultrasound findings include intraluminal thrombus, an enlarged vein, absent color flow signal, absent respiratory variation, and absent response to Valsalva maneuver or squeezing of the calf.

Deep venous thrombosis. Echogenic material fills and expands the superficial femoral vein. In the images on the right, the appearance of the proximal superficial femoral vein without (left) and with (right) compression are identical.

Deep venous thrombosis management includes treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin and analgesic pain control. Treatment of acute PE involves correction of hypoxemia with supplemental oxygen and immediate initiation of anticoagulation. Rarely, patients with hemodynamic compromise may require thrombolytic therapy or embolectomy.