Pancreatic trauma, inflammation, or ductal obstruction can lead to intrapancreatic enzyme activation, disruption of pancreatic ducts, and leakage of pancreatic secretions into adjacent tissues with consequent autodigestion and necrosis. The most common causes of acute pancreatitis are chronic alcohol consumption and acute pancreatic duct obstruction from biliary stone disease. Less common causes include hyper-triglyceridemia, medications, and trauma.

The diagnosis is based on clinical and laboratory finding; primarily severe upper abdominal pain in a patient at risk for pancreatitis, with elevated serum lipase. The role of CT in acute pancreatitis is to confirm the diagnosis, assess severity, and point to a cause (e.g. obstructing gallstone, pancreatic mass, cirrhosis). Imaging may be normal in mild or early disease, and its greatest value is in identifying subacute and late complications, such as necrosis, pseudocyst, and abscess formation.

Contrast-enhanced CT shows edema and inflammation as parenchymal enlargement, heterogenous attenuation, indistinct pancreatic margins, retroperitoneal fat stranding, and, if severe, peri-pancreatic fluid collections or frank pancreatic necrosis.

Ultrasound is less sensitive and specific for evaluating the pancreas than is CT, but it can be useful for detecting or following peri-pancreatic collections. When imaged by ultrasound, acute pancreatitis appears as an enlarged, hypoechoic pancreas, some- times with an adjacent fluid collection.

CT grading is helpful in determining prognosis and complications:

Pancreatitis Grading (Balthazar)

A Normal pancreas; 0% mortality, 4% complication rate

B Enlarged pancreas; 0% mortality, 4% complication rate

C Pancreatic inflammation and/or peri-pancreatic fat inflammation; 0% mortality, 4% complication rate

D Single peri-pancreatic fluid collection ; 14% mortality, 54% complication rate

E Two or more peri-pancreatic fluid collections and/or retroperitoneal air; 14% mortality, 54% complication rate

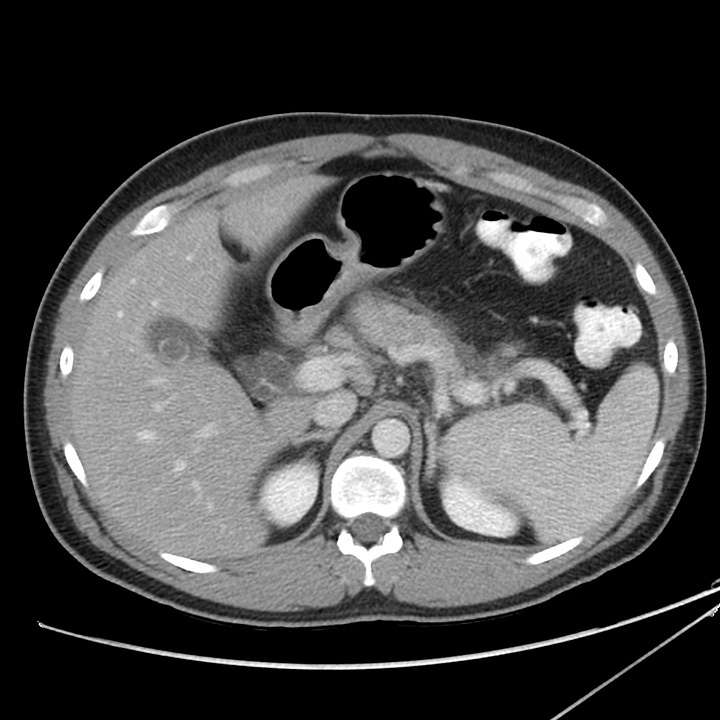

Gallstone pancreatitis. Mild peripancreatic edema anterior to the body of the pancreas. Distended common bile duct with tiny calcification at the ampulla (grade C).

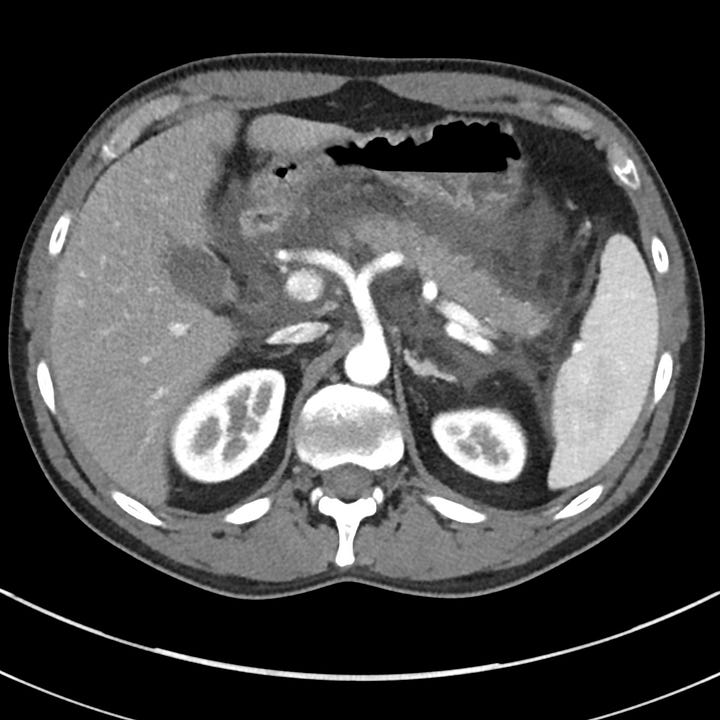

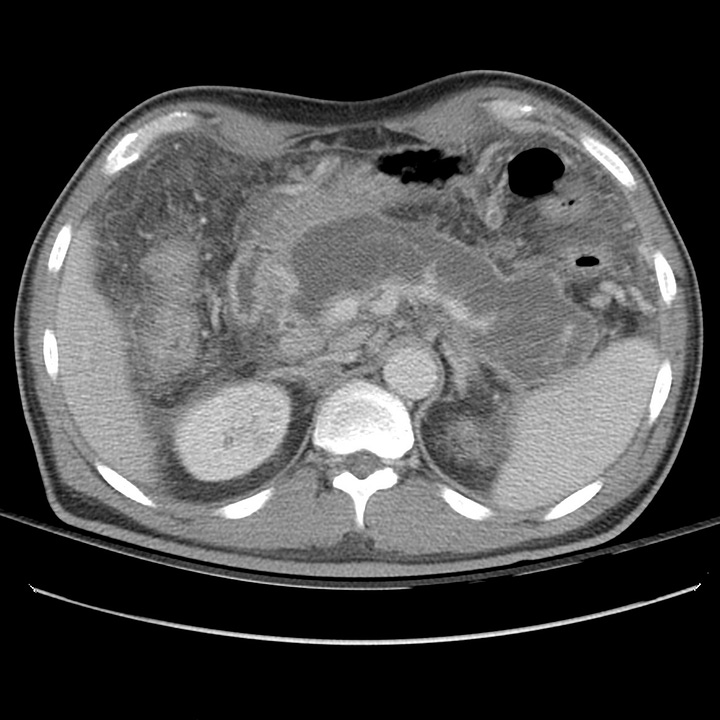

Moderately severe acute pancreatitis. Peri-pancreatic edema with retroperitoneal fluid surrounding the head and body of pancreas (grade D).

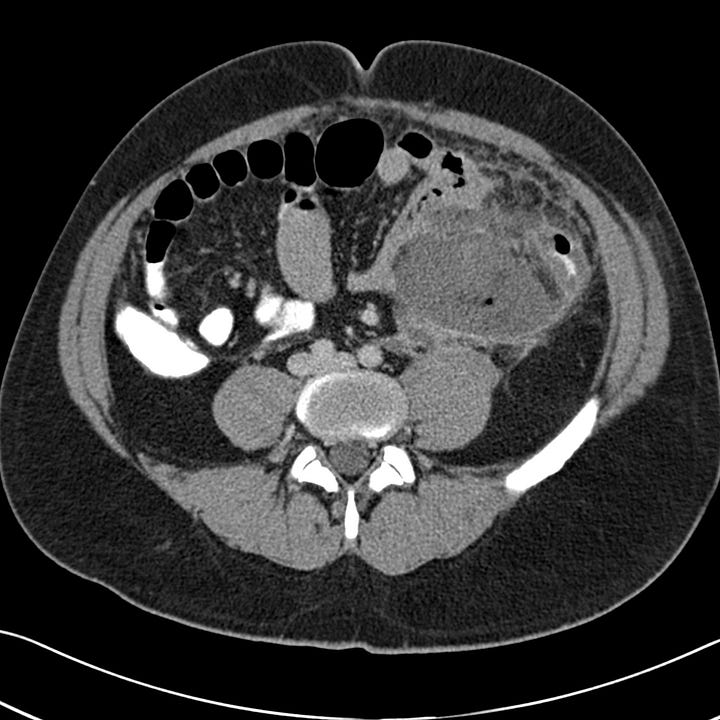

Severe acute pancreatitis. Multiple large peripancreatic fluid collections, including a well-defined left lower quadrant collection containing bubbles of gas (grade E).

Pancreatic necrosis may complicate acute pancreatitis and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Inflammation severe enough to cause cell death and liquefactive necrosis typically develops 24 to 48 hours after symptom onset. CT scans obtained in the first 12 hours may therefor be normal or only show mild inflammatory changes. Delayed imaging at ~ 3 days after symptom onset more sensitively detects necrosis than studies obtained at initial presentation.

There are three potential outcomes for pancreatic necrosis: resolution, formation of noninfected pseudocyst, or abscess. In severe pancreatitis, a pseudocyst (liquefied necrotic tissue contained within a fibrous capsule), can develop over a period of 3 to 4 weeks. Encysted tissue is prone to infection and abscess development.

Portions of the pancreas that fail to enhance after the administration of intravenous contrast are considered necrotic. Intra- or peri-pancreatic gas bubbles may also be seen. Pancreatic necrosis may be accompanied by peri-pancreatic fat necrosis, which appears as a heterogenous fluid collection adjacent to the pancreas.

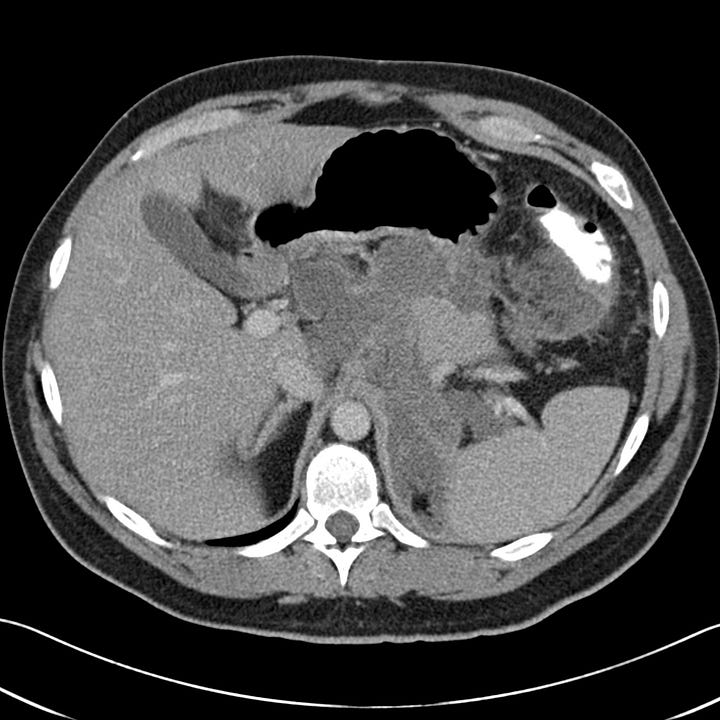

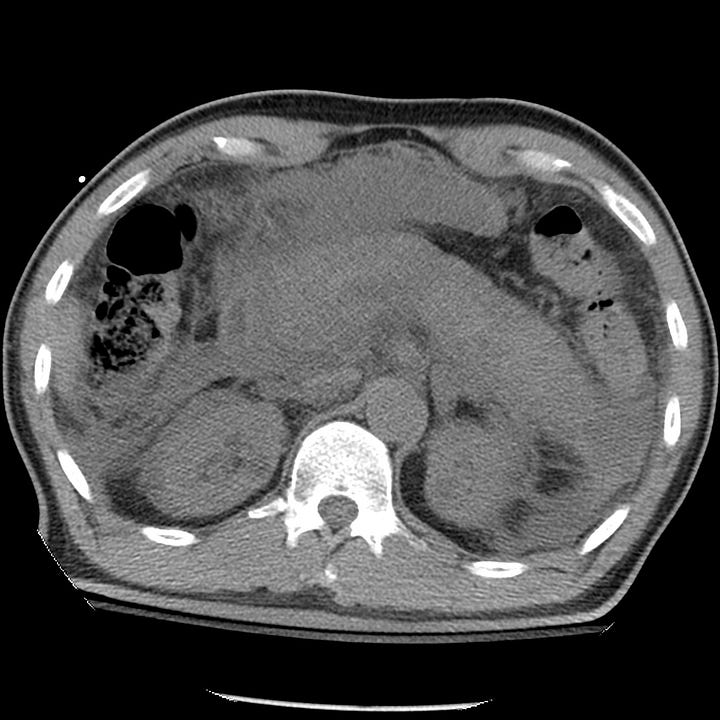

Acute pancreatitis with pancreatic necrosis. The pancreas is diffusely enlarged with extensive surrounding edema. Fluid is present in both anterior pararenal spaces.

At 18 days after symptom onset, most of the pancreas has been replaced by low-attenuation necrotic tissue contained by a thin, well-defined capsule. Mesenteric inflammatory changes persist.

Chronic pancreatitis is the consequence of persistent ongoing pancreatic inflammation with eventual glandular fibrosis, atrophy, and dystrophic calcification. Patients report a long history of intermittent epigastric pain that radiates to the back or recurrent episodes of acute pancreatitis. With sufficient pancreatic damage, the gland’s endocrine and exocrine functions fail, leading to malabsorption and diabetes. In contrast to the laboratory abnormalities seen in acute pancreatitis, lipase and amylase may be normal or only mildly elevated.

Abdominal or chest radiographs often show punctate or coarse upper abdominal calcifications distributed transversely across the epigastrium. These are primarily intraductal, located either within the main pancreatic duct or in the small pancreatic duct radicles. CT and ultrasound may show focal enlargement or atrophy of the gland, parenchymal calcifications, and pancreatic duct dilatation with ductal width greater than 5 mm at the head and 2 mm in the body and tail.

Chronic pancreatitis. Abdominal radiograph with multiple small calcifications superimposed on the L1 and L2 vertebral bodies.

Chronic pancreatitis. Atrophic pancreas with multiple punctate calcifications and mild pancreatic ductal dilatation. Small amount of perihepatic ascites.