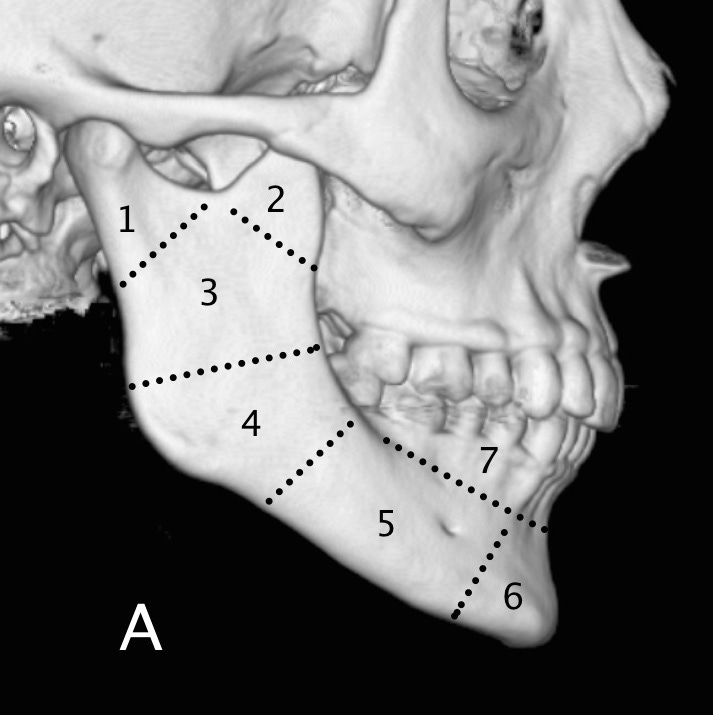

Mandible fractures are classified by location: condyle, coronoid process, subcondyle or ramus, angle, body, symphysis/parasymphysis and alveolus.

Mandible anatomy (1) condyle, (2) coronoid process, (3) subcondyle or ramus, (4) angle, (5) body, (6) symphysis/parasymphysis, (7) alveolus.

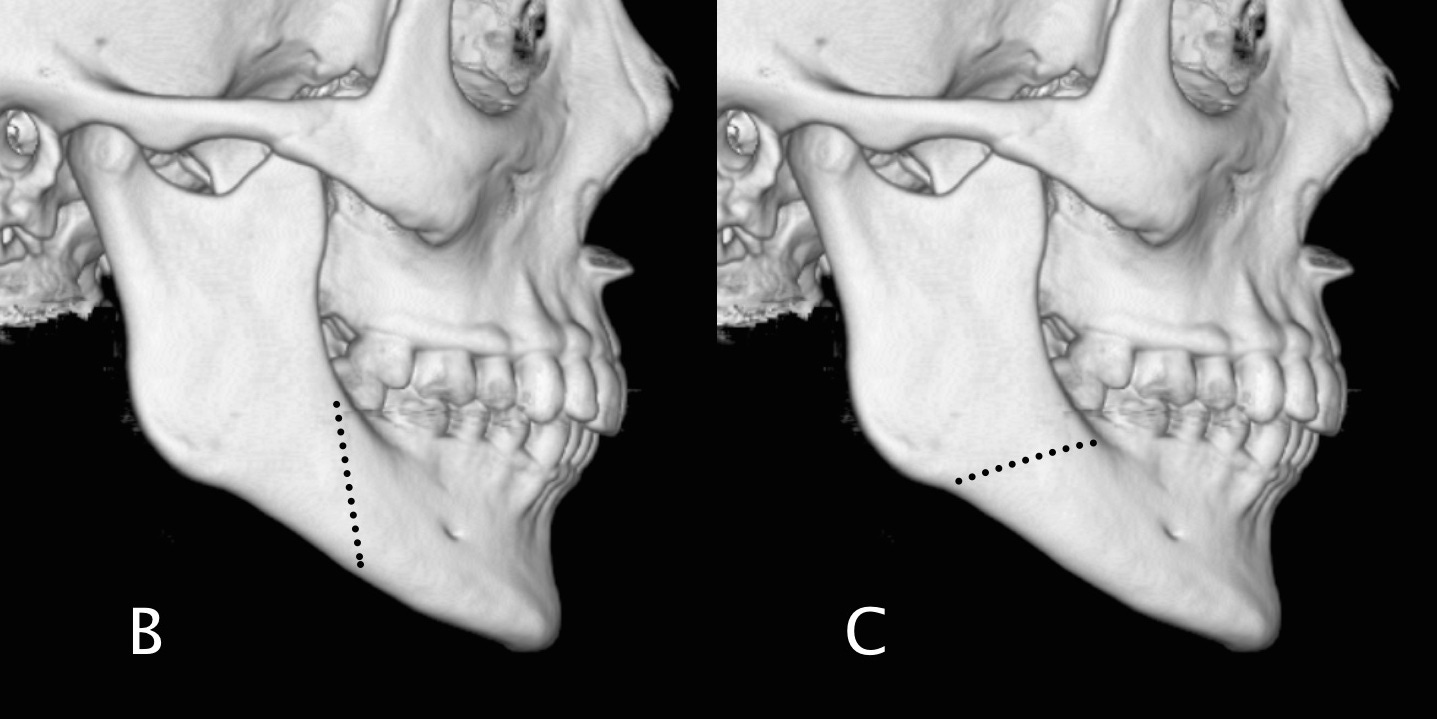

“Favorable” fractures are located more posteriorly at the superior mandibular margin and more anteriorly at the inferior margin; these fractures tend to be held in alignment by the pterygoid muscles. “Unfavorable” fractures, which have the opposite orientation, are distracted by normal muscular forces.

Fracture orientation: B Favorable orientation; likely to maintain alignment due to action of pterygoid muscles. C Unfavorable orientation; likely to displace without fixation.

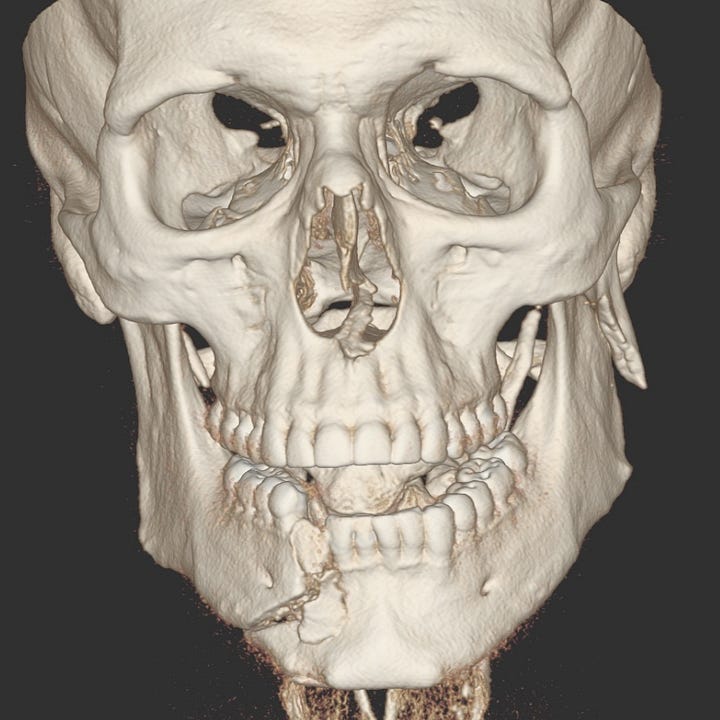

Because the mandible and the attached skull base form a ring, fractures often occur either at two sites or at a one site with associated temporomandibular joint separation. Frontal impact results in symphyseal fractures, while lateral impact, typical of assault injuries, leads to condylar, angle, or body fractures. Facial swelling, dental malocclusion, trismus, and intraoral bleeding are common clinical findings. A fracture that enters the root of a tooth is considered an open fracture, and these patients will require antibiotics.

Left condylar and right parasymphyseal fractures. The left mandibular condyle is laterally angulated and displaced with respect to the left body. The left body and symphysis are displaced to the left as a result of unopposed muscle pull from an “unfavorable” right parasymphyseal fracture.

Oblique radiographs or panoramic tomography can identify most mandible fractures. CT, which is usually available in the emergency setting, has the benefit of detecting any associated facial fractures and concomitant intracranial injury. Treatment depends on the location and conformation of the fracture and can consist of either maxillomandibular fixation, with arch bars and wiring, or open surgery with miniplate fixation.