Chest wall injuries

Chest

Sternal Fracture

Sternal fractures are a marker of high-energy impact and are seen in approximately 8% of patients with blunt thoracic trauma. Retrosternal hematoma, myocardial contusion, coronary artery tear, aortic laceration, and tracheobronchial tear are potential associated injuries.

Sternal fractures are not visible on supine portable AP chest radiographs, but they can be detected with a true lateral view. In practice, they are usually diagnosed on CT and are most commonly located 2 cm below the sternomanubrial joint. Retrosternal hematoma may be the consequence of great vessel injury or hemorrhage from small vessels; identification of normal fat between a substernal hematoma and the aorta indicates that the hematoma is not due to aortic rupture.

Sternal fracture. The upper portion of the sternal body is depressed by half its width at a point 4 cm distal to the sternal manubrial joint. No visible retrosternal hematoma.

Sternoclavicular dislocation

Sternoclavicular dislocation refers to anterior or posterior displacement of the medial clavicle relative to the sternal manubrium. Posterior dislocation, in which the clavicular head is displaced deep to the manubrium, typically results from a blow to the dorsal shoulder or to the anteromedial clavicle and can be associated with serious morbidity; as the medial clavicular head is driven into the soft tissues of the thoracic inlet, it can impact or injure the trachea, esophagus, recurrent laryngeal nerve, or great vessels. Anterior sternoclavicular dislocation results from a frontal blow to the ipsilateral shoulder, is more common than posterior dislocation, and carries less risk of associated injury.

The sternoclavicular joint is difficult to assess on plain radiographs. CT permits accurate characterization of the dislocation and any hematoma or vascular compromise. Sternal dislocations are usually treated by closed reduction in the absence of associated mediastinal injuries.

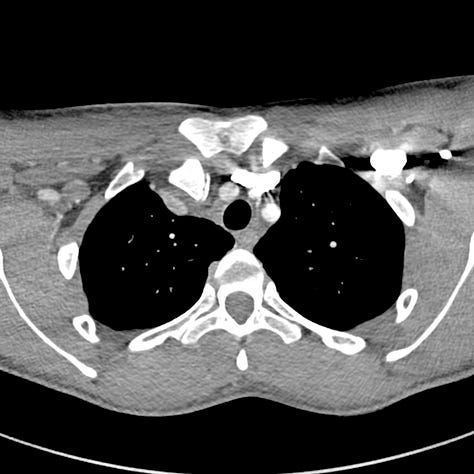

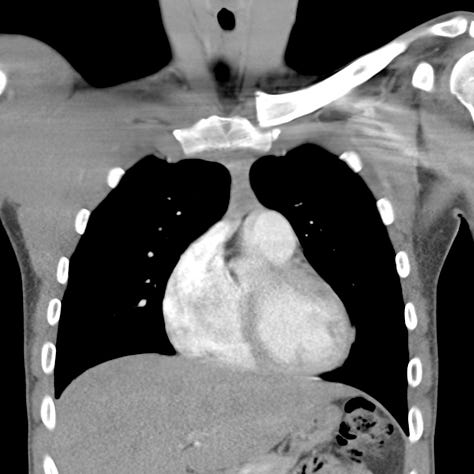

Posterior right medial clavicle dislocation. The right medial clavicular head is interposed between the subclavian vein and the right carotid artery. No associated vascular hematoma or definite injury. On coronal images, the right medial clavicle is posterior to the sternal manubrium. The left clavicle articulates normally.

Flail Chest

Flail chest is defined by the presence of five or more adjacent simple rib fractures or more than three segmental rib fractures; it can lead to impaired ventilation and respiratory failure in the trauma patient. The normal thorax increases in volume on inspiration. In flail chest, the affected side, lacking structural support, retracts inward under negative intrapleural pressure as the diaphragm contracts. On expiration, positive intrapleural pressure allows the free-floating segment of fractured ribs to bulge outward, referred to as paradoxical respiration.

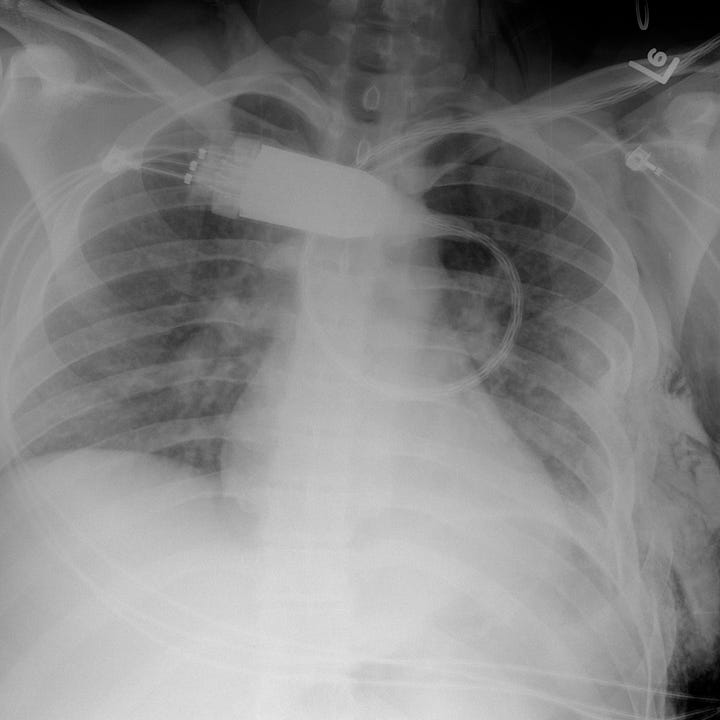

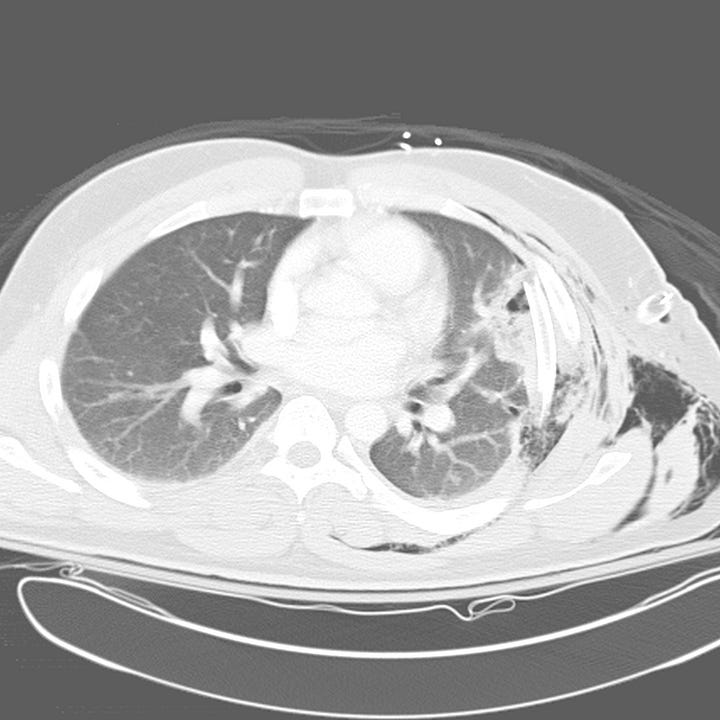

Flail chest. The left chest wall is deformed due to segmental left fifth through seventh rib fractures with adjacent opacity. Noncontrast CT reveals depressed segmental rib fractures with adjacent anterior segment left upper lobe pulmonary contusion and laceration. Extensive soft tissue emphysema. Left thoracostomy tube.

Flail chest is extremely painful, and patients display rapid shallow breathing. Hypoxia is usually a consequence of associated pulmonary contusion rather than simple hypoventilation. Management includes supplemental oxygen and analgesics and may require regional nerve blocks or epidural anesthesia in severe cases. Surgical plating of rib fractures is increasingly utilized in chest trauma and has been shown to reduce pain, pulmonary complications, length of mechanical ventilation, length of overall hospital stay and mortality. Indications include flail chest, chest wall deformity and failure to wean from mechanical ventilation.