Suprapubic pain, inability to void, gross hematuria, or microscopic hematuria greater than 25 red blood cells (RBC)/high-power field after trauma are all indications of bladder or urethral injury in the setting of abdominopelvic trauma.

Bladder rupture results from blunt external impact, frequently in conjunction with pelvic fractures and is classified as extraperitoneal, intraperitoneal, or combined intra- and extraperitoneal. Most are extraperitoneal and result from shearing forces that deform the pelvic ring or direct puncture by pelvic bone fragments. If the bladder laceration is below the peritoneal reflection, urine extravasation is limited to the extraperitoneal space.

Extraperitoneal bladder rupture. Contrast fills the prevesical space via two anterior defects in the bladder wall.

Intraperitoneal extravasation results from bladder dome disruption above the peritoneal reflection, and is often due to a direct blow to the lower abdomen in patients with a distended bladder. It tends to occur in intoxicated patients and belted passengers in motor vehicle accidents.

Intraperitoneal bladder rupture. Contrast is present in the bladder and surrounds the sigmoid colon in the peritoneal cavity. A large clot is evident in the bladder.

Bladder contusions and mural bladder hematomas are relatively benign, with a normal or teardrop-shaped bladder on cystography; management is conservative with observation for resolution of hematuria.

Standard abdominal CT scanning for trauma readily identifies perivesical fluid or pelvic fractures adjacent to the bladder, but it is insensitive for detection of small leaks.

A dedicated CT or plain film cystogram, in which contrast is directly instilled into the bladder via a Foley catheter, more accurately excludes small bladder ruptures. In severe polytrauma requiring immediate laparotomy, cystography is usually bypassed, and the bladder is directly evaluated intraoperatively.

Urethral injuries, while uncommon, contribute to significant long-term morbidity from complications including impotence, stricture formation, urinary retention, or incontinence. They most commonly involve the posterior urethra and are seen less frequently in women, primarily because of shorter urethral length. In blunt trauma, posterior urethral injury is almost always associated with pelvic fractures. Anterior urethral injuries (penile, bulbar urethra) are more frequently due to blunt trauma to the perineum (straddle injuries) and may present years later with complications from stricture formation.

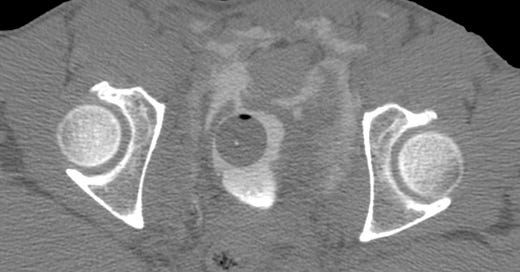

Traumatic urethral disruption. Open book–type pelvis fracture with left acetabular, iliac, superior and inferior pubic rami fractures, and pubic symphysis diastasis. A retrograde urethrogram shows extravasation of contrast material into the extraperitoneal space without any filling of the urinary bladder.

The male patient with pelvic trauma who presents with gross hematuria, blood at the urethral meatus, edema or hematoma of the perineum or penis, or with a “high-riding” or boggy prostate after a pelvic fracture is likely to have a urethral injury. In these patients, a retrograde urethrogram should be performed prior to the insertion of a Foley catheter, which could enlarge a laceration or contaminate a previously sterile hematoma.