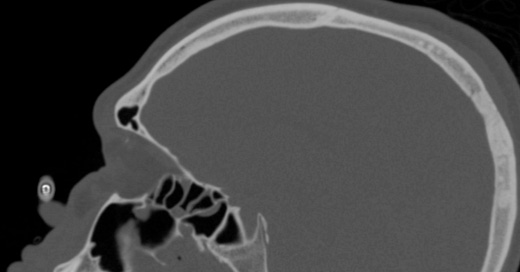

Atlantooccipital dislocation (AOD) is a consequence of very high-energy trauma; usually diagnosed at autopsy rather than on imaging studies. In AOD, the skull is dislocated with respect to the lateral masses of C1, and this can be directly assessed on CT by evaluating the congruity of the atlantooccipital articulations. Displacement can be along either the transverse or craniocaudal axis and is usually associated with marked prevertebral soft tissue swelling.

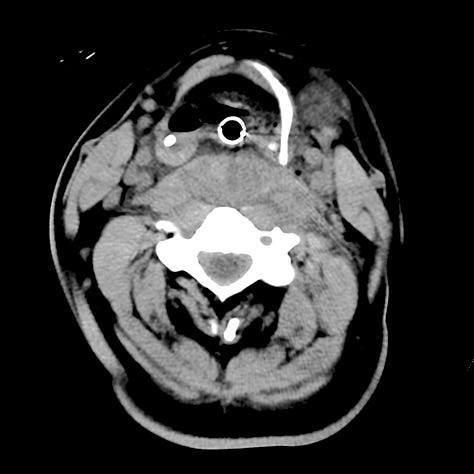

Atlanto-occipital dislocation. Abnormally widened basion–dens interval, basion–axial interval. Anterior subluxation of the lateral mass of C1 with respect to the occipital condyle and widened C1-occiptial condyle distance. Marked prevertebral soft tissue swelling at the level of the hyoid bone. Subarachnoid hemorrhage surrounds the upper cervical spinal cord.

Complete AOD (dislocation) is a fatal injury, but partial AOD (subluxation) may be compatible with life. To ensure detection of an unstable but potentially survivable injury, the atlantooccipital articulation should be specifically evaluated on any lateral radiograph or cervical spine CT obtained for trauma.

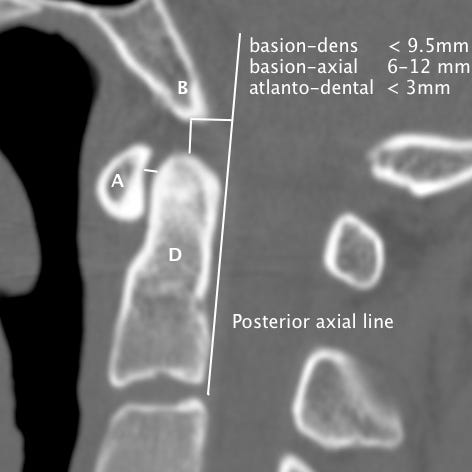

The most useful measurements are the basion–dens interval, the basion–axial interval, and the atlantodental interval, which assesses integrity of the transverse C1 ligament.

Normal craniocervical relationships on CT. The basion–dens interval (B–D) should be < 9.5 mm, the atlantodental interval (A–D) should be ≤ 3 mm in adults and ≤ 5 mm in children, and the basion–posterior axial line (B–PAL) interval should be between 6 and 12 mm on a sagittal CT reconstruction. The occipital–C1 and C1–C2 articulations should be symmetric and congruent on coronal and parasagittal images.

Only if they never lost them at the time of injury and that would be very unusual, but not completely impossible.

If the patient survives, can they eventually regain most of their abilities?