While atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation typically results from motor vehicle accidents and sports-related injuries in older adolescents and adults, it may be seen in children without obvious injury. In trauma, disruption of the alar ligament, atlantoaxial joint capsule, and transverse ligament permits hyper-rotation of C1 relative to C2 with widening of the at- lantodental interval. Patients present with their head tilted to one side and rotated to- ward the opposite side.

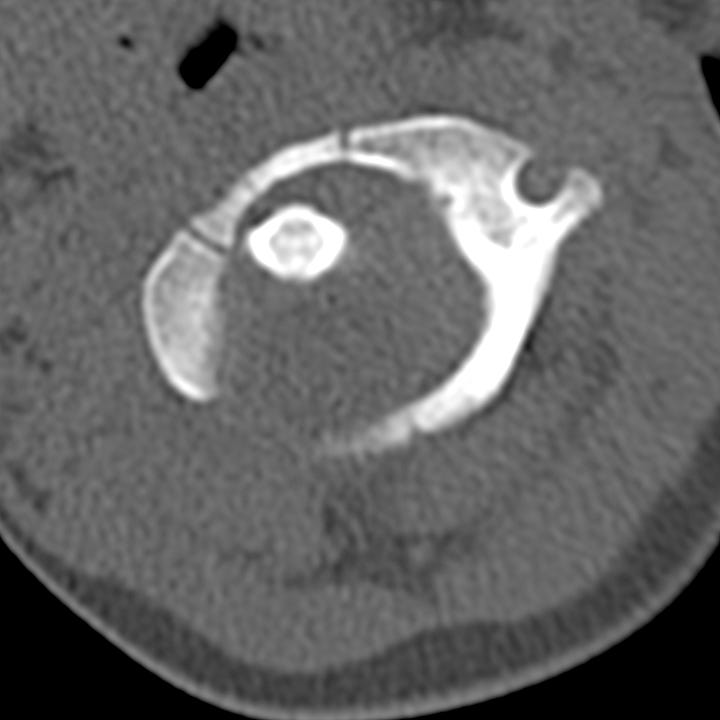

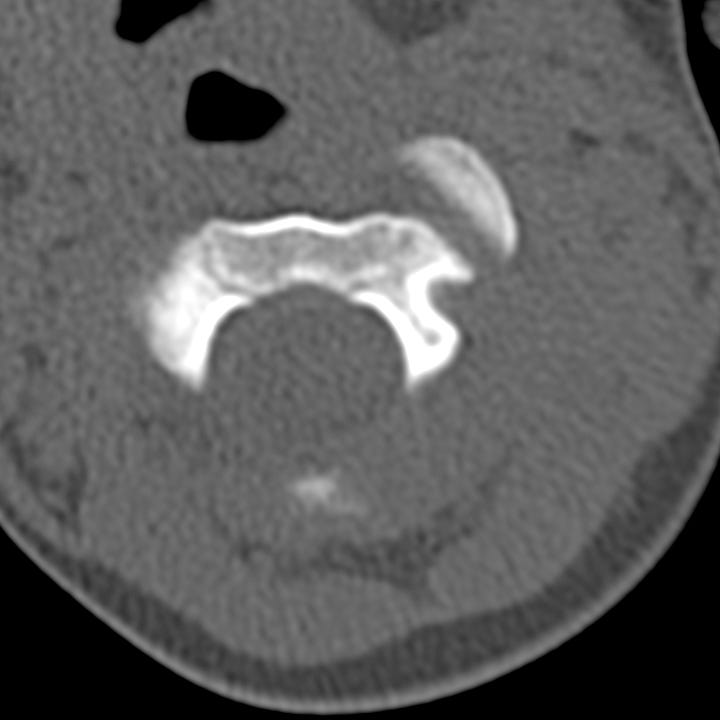

AP or odontoid radiographs will show asymmetry of the lateral atlantodental in- tervals. CT is diagnostic and demonstrates rotation of the C1 ring with respect to the C2 lateral masses. If not clinically obvious, dynamic imaging with scanning before and after voluntary head turning can establish whether or not subluxation is fixed.

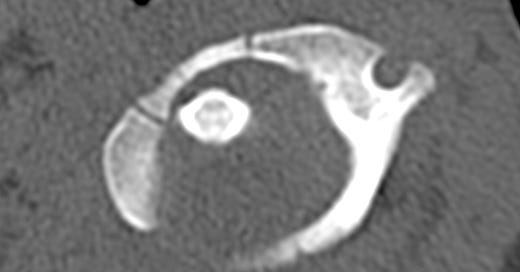

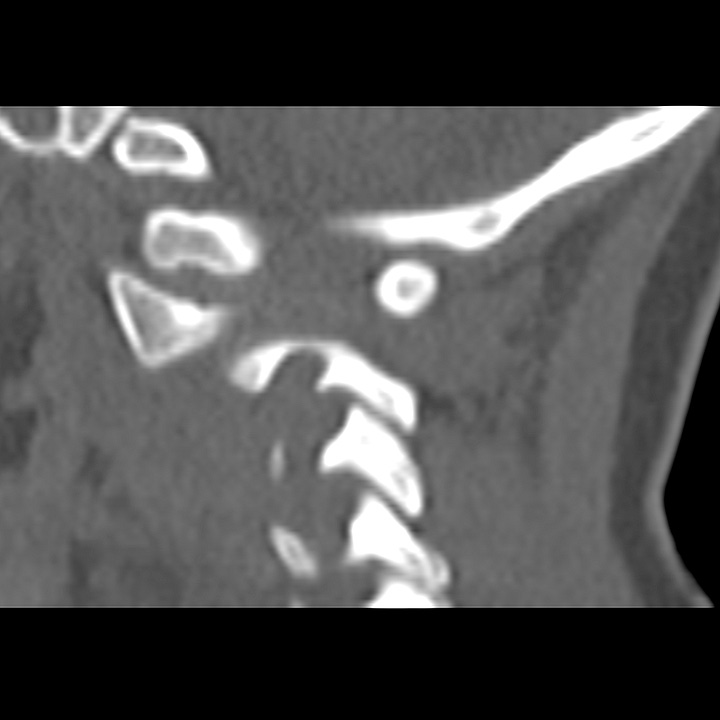

Atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation in a child. C1 is rotated to the right with respect to C2. The left C1 facet is anteriorly displaced with respect to C2. While the C1/C2 facets align on the right para-sagittal reformation, the left lateral mass of C1 is displaced anterior to the articulating surface of C2 on the left para-sagittal reformation (lower right image).

Fixed subluxation can be reduced by cervical traction followed by active range of motion (ROM) exercises. Rarely, C1–C2 fusion can be considered for persistently fixed and painful rotation.