Acute subdural hematomas occur when cortical veins that traverse the subdural space are torn under cerebral acceleration or rotation. Blood accumulates between the inner (meningeal) layer of the dura, which is firmly attached to the skull, and the smooth arachnoid membrane loosely adherent to the surface of the brain. Uncommonly, a primary parenchymal or subarachnoid hemorrhage can disrupt the arachnoid membrane and rupture into the subdural space.

Subdural hematoma is associated with a skull fracture in less than 50% of cases and is typically a “contrecoup” injury that results from recoil of the brain away from the inner surface of the skull opposite the site of impact. As the hematoma compresses small cortical vessels, the underlying brain can become ischemic. Larger hematomas result in compartmental shift and potential cerebral artery compromise.

Especially in younger patients, an acute subdural hematoma indicates significant energy transfer and is often associated with severe parenchymal brain injury, brain herniation, and cerebral ischemia. Hematomas due to minor trauma are more common in the elderly and in patients with cerebral atrophy. Volume loss and enlarged CSF spaces allow the brain to move more freely in the calvarium and compromise the ability of the brain to tamponade low-pressure hemorrhages. In such patients, enlarged extra-cerebral space limits the degree of parenchymal compression and ischemia.

Acute subdural hematomas are crescentic, hyperdense, and usually homogeneous. They can extend along the entire hemisphere and are confined by the falcine and tentorial dural reflections. In contrast to most epidural hematomas, the extend of a subdural hematoma is not limited by calvarial sutures. Venous hemorrhage is usually more gradual than arterial bleeding, and subdural hematomas can develop more slowly than epidural hematomas. Nonetheless, large subdural hematomas can cause acute and severe neurologic deterioration and often require urgent evacuation. Hematoma thickness or subfalcine shift of 2 cm or greater is associated with a particularly poor prognosis.

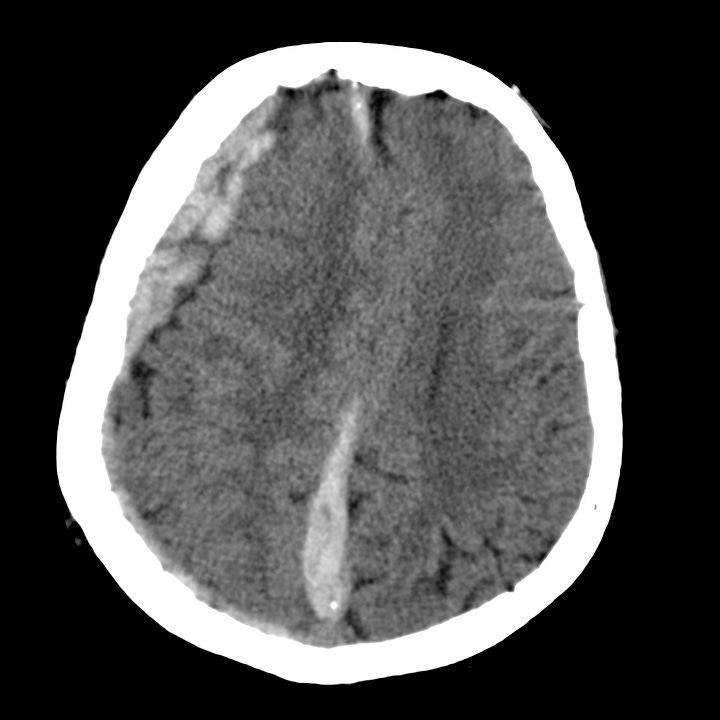

Acute subdural hematoma. 1.8-cm hyperdense left holohemispheric subdural hematoma with traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage, 1.6-cm subfalcine shift, compression of the left lateral ventricle, and trapping of the right lateral ventricle.

Acute subdural hematoma. Large right hematoma with prominent hyperdense frontal, posterior parafalcine, and tentorial collections.

The density of subdural clot can overlap with that of calvarial bone on narrow CT windows optimized for evaluation of brain parenchyma, and small hematomas can be difficult to detect. To avoid this error, head CT obtained for trauma should always be viewed at both narrow and wide (subdural) window settings.

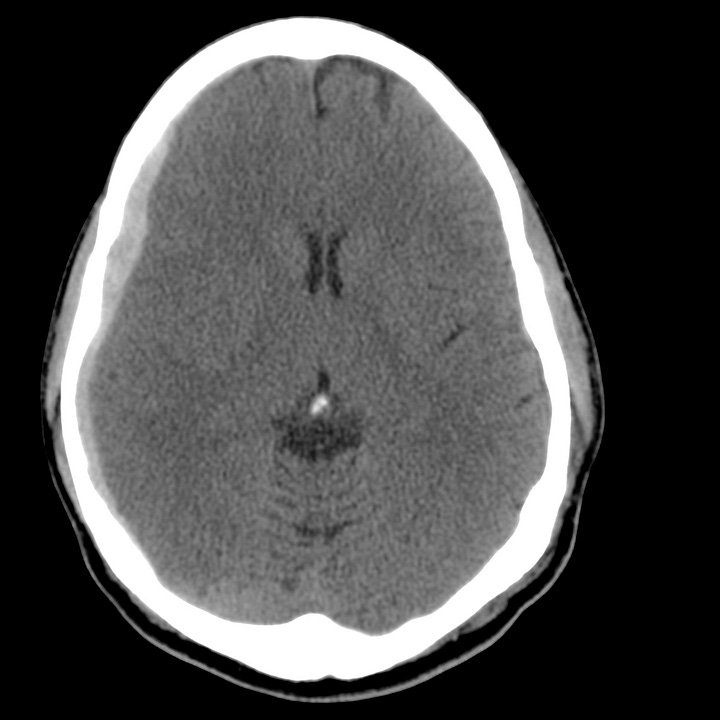

Window and level in detecting subdural hematoma. On the left image, CT window = 80 (brain) and shows subtle effacement of right frontal sulci, but is otherwise apparently normal. The right image, with CT window = 170 (subdural), clearly shows a 5-mm right frontotemporal subdural hematoma.